Stepping into the cavernous lecture hall, Matthew Zur looked around at the 300 other students – and felt alone.

A third-year student at the University of Central Florida (UCF), Zur’s decision to seek a business degree felt iffier by the day. His fading dreams of being a teacher, which had come from sunny days at summer camp throughout his teenage years, had been pushed away in pursuit of a career with better status. His father, who taught at Fletcher Middle School, had urged him to stay away from education.

Worse, his father’s colleagues grumbled that Zur was too good to waste his life as an educator.

Though a business degree had matched the academic aesthetic Zur imagined college should be – most of his friends were also seeking six-figure futures – Zur was tired of all the brain-numbingly dull calculations and marketing gimmicks. Every class felt inherently wrong, and his motivation had started to drain.

He dragged into the lecture hall for another pre-requisite to his business degree with wary hope – which was immediately dashed.

Grimacing, Zur watched the professor project students’ answers to the crowd of coffee-deprived faces. With curt, painful quips, the professor ridiculed every line of a student’s work, pointing and snickering while the targeted student sank in his seat.

“I could always tell how interested I was in a class based on where I sat. And in this class, I started in the middle and by the end of the semester, I was right by the door,” Zur said.

His professor’s sneer and pinched comments echoed in his mind, and a determination hardened.

What am I doing here? Zur thought, looking at the deadened faces of his peers trying to avoid eye contact with the professor. Then it came to him: a cold calculation leading him to a spiritual epiphany.

This was not where he was supposed to be. He had to untangle himself from the lackluster vision of a cubicle life. He had to trust the feeling that had grown in him, quiet but persistent.

“I had to become a teacher,” he stated. “Because if teaching is like an algebra equation and he’s on the bad side of it, at least I can be on the good side of the equation, and we can cancel each other out.”

From panic to peace

A decade later, Zur’s AP Capstone and Debate students saunter into class each morning to be surrounded by a hodge-podge of pop culture. Posters for Super Pets and Jujitsu Kaisen litter the walls, alongside a mosaic of album covers, curated by Zur himself.

Before sitting down, a couple students straggle to check on Room 125’s new pet snake, Zeppelin, others chatter as they unwind from the stress of other courses. A few huddle around Zur himself, asking questions about the song he has playing on the screen or what the day’s itinerary is.

As Spotify opens for the umpteenth time, the classroom goes quiet, students opening Genius lyrics and rereading verses. Zur, ever the gently chaotic personality, leaps to slowly bring the volume bar down before facing the class.

“The Jags are back, guys!” he announces with a grin while hoisting a box of Publix sprinkle cookies, the traditional reward for the occasionally won football game.

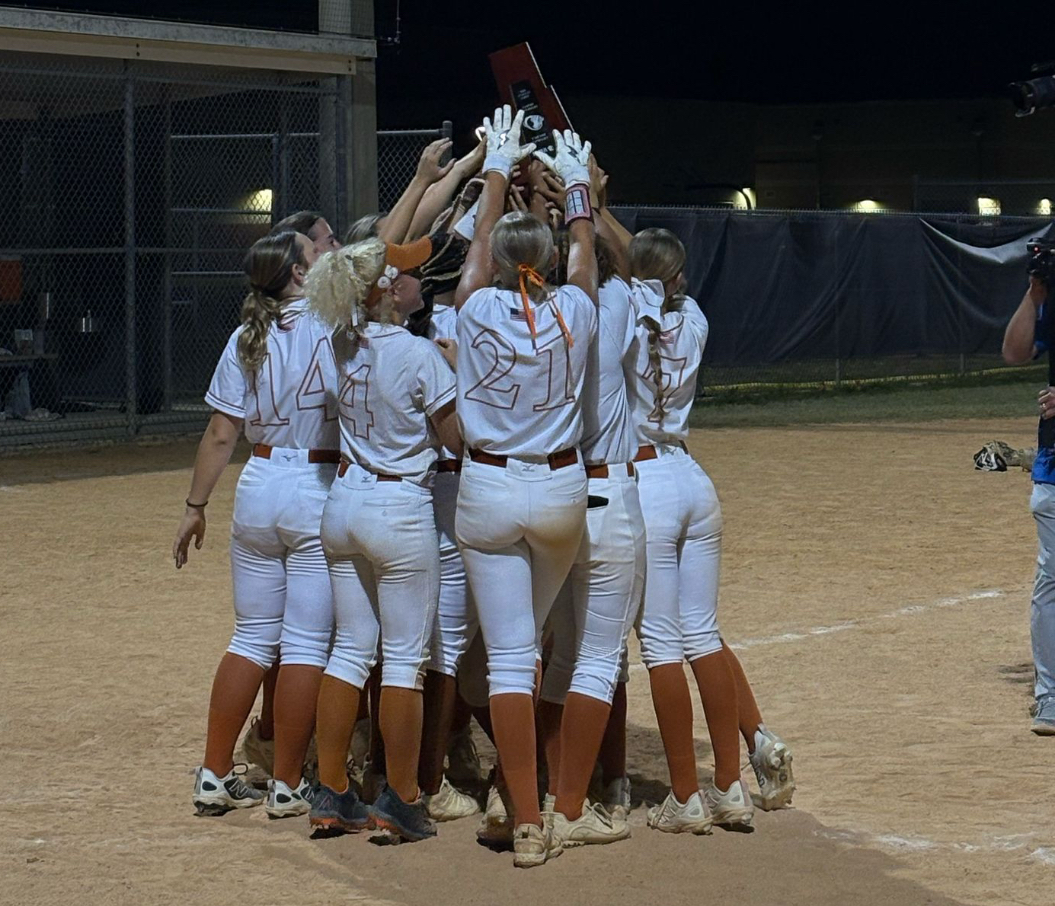

When he’s not lecturing and guiding in class, he’s always a fixture at Atlantic Coast events – cheering in the stands at football games, helping behind the scenes at StingrayCon, or stepping in as chaperone for the Brain Brawl team.

“Zur is the kind of teacher I would want my own son to have. He’s someone students can relate to, look up to, and learn from. We are better as a school because he’s part of our team.”

Dr. Blair Chambers, assistant principal in charge of student scheduling among various other duties, said Zur offers students a mix of approachability and dependability with what she described as “presence, patience, and purpose.” He’s never had a bad day, or at least hinted so, Chambers said, because he ensures the education and mental health of his students come first.

“Zur’s focus never wavers from what matters most: the kids,” Chambers said. “When he’s on campus, he is here for the kids, and he makes that evident through his tireless work to help students find themselves and their passion.”

Despite the cheerful persona seen in the halls today at Atlantic Coast High School, Zur was far quieter during his teenage years at Nease High School – the product of being a teacher’s son and knowing some silence was always appreciated in a rowdy classroom.

The quiet had never been a good place for Zur, though. Since childhood, Zur dealt with anxiety and ADHD, not receiving professional help until well into his adult years. This led to depression throughout college.

“I’d have panic attacks in my room… the silence of being in there, and the ceiling fan would feel absolutely wild, like a tornado.”

As a child, mental health was still an undiscussed realm. Under the surface of stellar grades – he was an Advanced Placement student and a staff writer for the school newspaper – Zur struggled to become more independent in high school, getting progressively later and messier on assignments.

“My backpack was a nightmare,” Zur said. “It had papers in chronological order of when I got them since August. It was like a filing cabinet only I knew the organization of, and it was not effective at all. It was very bad.”

With the gradual buildup of academic expectations, Zur insulated himself within a supportive group of friends. Sharing every interest from Call of Duty to Jack Johnson songs, his merry crew of 15 was forged from lunches in their favorite history teacher’s classroom to days out at the beach.

“I think I escaped the uncomfortable parts of high school by just having friends who were dweebs, real turbo-nerds,” he said with a smile.

Zur stated that his inner circle played a large role in where he decided to go to college. As his friends started pursuing careers in finance, it seemed like the logical decision for Zur to follow.

The newfound freedom of college had been exhilarating at first, but Zur’s mental health went into a decline at UCF with no teachers or parents to remind him of what was due. Even though his friends were in the same program as him, the increase in alone time became less of a chance to grow and more of a chasm he could not escape.

It took years of boredom and one infuriating professor to spur Zur into making the choice to switch to education. However, even as he sat in his counselor’s office, signed major change form in front of him, he couldn’t get the disappointed voices out of his head.

Am I sure about this? How will I know this is the right decision? Listening to his father’s disappointed reaction over the phone when he confessed he’d changed majors, Zur’s carefully content life was now a whirlwind of uncertainty.

“Other people’s expectations of me were driving me,” Zur said. “But once I got my mental health a little bit better, it was mostly expectations of myself.”

Trying to navigate his mental health recovery while staying in academic good graces was a battle Zur fought since elementary school. After changing his major to education, he spent a two-year sabbatical working at local schools and improving his mindset before applying to the University of North Florida, where he slowly began to thrive.

When asked what made him pursue education, Zur’s thoughts always returned to the past. His summers at camp led to dreams of continuing to be a counselor, or something focused on psychology, like becoming a therapist or researcher.

“The whole time from five to eighteen, I was going to three different schools, but I was at this one camp every single summer,” Zur said. “And so, it provided consistency and structure and a space where I could have value and be somebody. And when you’re a young adult, feeling like you are someone, it’s very, very important.”

Finding harmony

Zur wasn’t sure what his future would entail.

His career choices had felt murky since high school. His personality seemed split between two opposite directions: one was the mellow, academic-inclined blur of a dream he had come to college for, and the other was something wilder, more eclectic: a life of music.

After all, he had rock star in his genes.

A professional singer since dropping out of middle school, Zur’s mother, Mrs. Carol Bristow-Zur, has played with the 70s rock band, .38 Special, who toured America, Europe and Japan. Even featuring in iconic songs like, ‘Rockin’ into the Night’, Mrs. Zur lived a life of late flights and screaming mics, hopping from band to band across the world.

The strobe lights and wailing guitars dimmed when she met Zur’s father in the apartment complex she lived in during time in Jacksonville. They met again at Mayor Donna Deegan’s wedding, where she was the performing singer.

Despite her love for the stage, Mrs. Zur chose to settle down in favor of a stable life for Zur and his older sister. She hadn’t wanted their lives to be a constant move from one city to another, the way hers had been the previous decade. Even so, she continued to take her place on stage well into Zur’s childhood, whether it was the St. Augustine Amphitheatre or a humble county fair.

“My mom, she’s always singing around the house,” Zur said. “And that made me act the exact same way when I’m at home; music is constantly playing. There are always songs going through my head.”

Throughout his childhood, Zur would find himself watching his mom play her third show of the week at a new bar in Jacksonville. Squinting in the dim lighting, he’d work on his math homework or fiddle with his Gameboy.

Though her performances had been common enough to be boring for young Zur, he now says seeing his mother continue her love for singing is inspirational. Between work hours, Zur unwinds by jamming in a band with his friends and is always on the prowl for new music to add to his playlists.

“I listen to a lot of music,” Zur said. “I think in the same way that people who aren’t picky with food do: I just want to try stuff. I don’t care what it is. Oftentimes there’s experiences underneath there, and maybe I can relate to them, or it’s an interesting story.”

Zur’s love for music, both stemming from his mom and his own discoveries, has come to define a lot of his mentality. He uses the same curiosity he has for an artist’s inner thoughts to form closer relationships with students. He advises other teachers to not be afraid to accept that mistakes can be made on both ends.

“Find what you have in common with them and don’t be afraid to humanize yourself. If you can foster a place where people are not afraid to say the incorrect thing, they’ll say what they feel and you get an insight into who they are and what makes them tick,” he said.

The board of Polaroids in Zur’s class features faces spanning his years of working with students. Zur mentioned how he loves to capture moments his students will forget over time, just chatting with a friend or laughing at a joke that fades by the next day.

Being able to fondly look back at his students and their memories reminds Zur of the impact he made. To Zur, the most rewarding part of being a teacher is honoring the achievements his students accomplished over the years – and his efforts are appreciated.

“When I walk into Mr. Zur’s, I already know I’m going to laugh at his lame jokes,” Sarah Leite, one of Zur’s students, says. “He inspires me to become a better person, and that’s why I’ll always appreciate coming to his class.”

Nevertheless, Zur still works to improve his connections with students. His wallflower past went from shrinking away from his own professors to becoming a point of empathy in his own classroom. Today, Zur encourages discussions of mental health with his students, using his own experiences as a comforting message of overcoming the chasm.

“I’m not the best, but I’m trying to be better every single day,” he said, whether that be in his personal life or standing at the front of the classroom. “Even if it’s something like making cinnamon rolls, or playing with my cats more, or making my students’ work feel more meaningful… we’re making their life experiences feel important – and validating the way they feel.”